Before you start#

Definition of terms for a common understanding of risk#

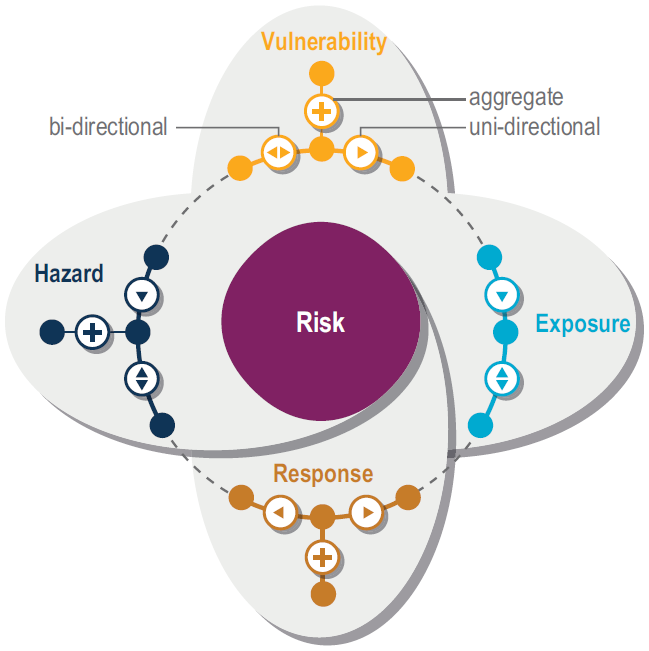

Fig. 2 Source: Figure 1.5 in Ara Begum et al., 2022.#

Risk is defined as “[t]he potential for adverse consequences for human or ecological systems, recognizing the diversity of values and objectives associated with such systems.” (Reisinger et al., 2020, p. 4). It can be calculated as an interplay of climate hazards (e.g. frequency and intensity of droughts), exposure (e.g. a land area where agriculture is conducted) and vulnerability (e.g. presence or absence of irrigation) and also includes human responses (Ara Begum et al., 2022).

A climate-related Hazard is “the potential occurrence of a natural or human-induced physical event or trend that may cause loss of life, injury, or other health impacts, as well as damage and loss to property, infrastructure, livelihoods, service provision, ecosystems and environmental resource” (IPCC, 2022, p. 5) such as floods, droughts, heatwaves, and other extreme weather events. Climate change can alter the frequency, magnitude, and duration of extreme weather events which are especially relevant for a climate risk context.

Vulnerability is defined as “the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected and encompasses a variety of concepts and elements, including sensitivity or susceptibility to harm and lack of capacity to cope and adapt.” (IPCC, 2022, p. 5). It further includes “all relevant environmental, physical, technical, social, cultural, economic, institutional, or policy-related factors that contribute to susceptibility and/or lack of capacity to prepare, prevent, respond, cope or adapt” (UNDRR, 2022, p. 19). The Climate Risk Sourcebook (Zebisch et al., 2023, p. 19) defines the reduction of vulnerability as “one of the biggest levers” for climate risk management.

Exposure refers to “(t)he presence of people, livelihoods, species or ecosystems, environmental functions, services, and resources, infrastructure, or economic, social, or cultural assets in places and settings that could be adversely affected” (Oppenheimer et al., 2014, p. 1048).

Response: In addition to hazard, exposure and vulnerability, climate risk also depends on how a society adapts to climate events. Adaptation responses (also called climate risk management interventions or options) may entail planned adaptation (physical constructions, nature based solutions, planned relocation) or autonomous adaptation (behavioral changes or forced migration).

Stakeholders, Experts, Priority Groups, Users#

Stakeholders from policy (e.g. ministries, agencies, government and state offices, agencies), relevant public and private sectors.

Experts are scientists, practitioners or policy advisors with robust knowledge (e.g. universities, institutes, climate and meteorological services).

Priority groups: Representatives from vulnerable or marginalized groups, exposed areas, or other relevant communities in society.

Users are directly related to the (technical) use of the CLIMAAX Climate Risk Assessment Framework and risk workflows.

Supporting Definitions#

Adaptive Capacity is “[t]he ability of systems, institutions, humans and other organisms to adjust to potential damage, to take advantage of opportunities or to respond to consequences” (MEA, 2005).

Climate Risk Management (CRM) includes plans, actions, strategies or policies that “reduce the likelihood and/or magnitude of adverse potential consequences, based on assessed or perceived risk” (IPCC, 2023, p. 2921). CRM has the goal of reaching resilience and adaptation.

Risk Outcome is the quantitative result(s) of the Risk Workflow(s) as part of Risk Analysis and feeds into the Key Risk Assessment for their contextualisation and evaluation.

Note

Further supporting definitions will be continuously added according to the need of (pilot) regions and applicant communities.

Conceptual Background#

A CRA needs to stand on solid ground, targeting and enabling success factors, while simultaneously providing operational steps for practical implementation. The conceptual background of the CLIMAAX Framework is organized around a three-pronged design:

Principles – a collection of principles, norms, and recommended practices that forms a grassroot, community-based standard on how climate risk assessment can facilitate transformative adaptation.

Technical choices – clear technical specification of considerations needed for conducting a CRA such as selection of scenarios, use and selection of local data, timeframe, spatial scale.

Participatory processes – approaches for implementing an inclusive CRA which support local and regional communities in identifying shared goals and priorities for coordinated CRM efforts.

Sources#

Ara Begum, A. et al. (2022) ‘Point of Departure and Key Concepts.’, in H.-O. Pörtner et al. (eds) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 121–196.

IPCC (2022) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by H.-O. Pörtner et al. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

IPCC (2023) ‘Annex II: Glossary’, in V. Möller et al. (eds) Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1st edn. Cambridge University Press, pp. 2897–2930. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.

MEA (2005) ‘Appendix D: Glossary’, in R. Hassan, R. Scholes, and N. Ash (eds) Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Current States and Trends. Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group. Washington, DC: Island Press, pp. 893–900.

Oppenheimer, M. et al. (2014) ‘Emergent risks and key vulnerabilities’, in C.B. Field et al. (eds) Emergent risks and key vulnerabilities. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1039–1099.

Reisinger, A. et al. (2020) The Concept of Risk in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report: A Summary of Cross-Working Group Discussions: Guidance for IPCC Authors. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

UNDRR (2022) ‘Technical Guidance on Comprehensive Risk Assessment and Planning in the Context of Climate Change’. Available at: https://www.undrr.org/media/79566/download?startDownload=true (Accessed: 26 April 2023).

Zebisch, M. et al. (2023) Climate Risk Sourcebook. Bonn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).